EDITOR’S NOTE: This article is excerpted from Elmer Ogawa: After hours with Seattle’s forgotten photographer, a biography of the late Japanese American photojournalist written by Tacoma Daily Index editor Todd Matthews. This is the second installment of three parts that began on Mon., Dec. 7, continues today, and concludes on Fri., Dec. 11. More information is available online at wahmee.com.

IN THE FALL of 1954, a twenty-two-year-old Japanese American woman named Pat Suzuki arrived in Seattle as an understudy for a touring production of Broadway’s “The Teahouse of the August Moon” that was being staged at the Moore Theatre. Suzuki was a diminutive figure—two inches shy of five feet tall, just under one hundred pounds, childlike bangs, and a long, black pony tail that draped down her back. It was her voice, however, that was outsized and turned heads.

One afternoon, Suzuki and a friend poked their heads into The Colony, a new nightclub at the corner of Fourth Avenue and Virginia Street, on the bottom floor of the nine-story Claremont Apartment Hotel. The club wasn’t open, and the owner, Norm Bobrow, mistook Suzuki and her pal for trespassers and nearly kicked them out of the club.

“What do you kids want in here?” Bobrow asked, annoyed.

“Just casing the joint,” Suzuki replied sassily as her companion scampered out of the club. “And I’m no kid.” Suzuki explained that she was with the touring production of “Teahouse” and looking for a side gig singing in a nightclub. Would Bobrow allow her to audition?

Bobrow reluctantly agreed. Five minutes later, he was floored. Suzuki had the gig.

What followed was the rise of the most popular Seattle nightclub singer during the late 1950s. Suzuki moved into a suite in the hotel and turned The Colony into a nightlife destination. Local columnists wrote rave reviews and adoring profiles of Suzuki. A Seattle Times columnist described her as “100 pounds of Nisei dynamite with a voice that could loosen the tiles on Broadway’s towers.” Famous musicians, actors, and bandleaders passing through Seattle made a point of stopping at The Colony to see her. Lawrence Welk heard Suzuki perform and phoned her personally to book her on his show. She flew to Hollywood to appear on a television show hosted by Frank Sinatra. Bing Crosby was at The Colony one evening and was so awed by her talent that he put her in touch with RCA Victor and guided her toward a recording contract. In 1959, Crosby, writing the liner notes for Suzuki’s album The Many Sides of Pat Suzuki, recalled his visit to The Colony to see Suzuki perform:

Halfway between the chatter and chateaubriand, the lights dimmed in their traditional theatrical fashion, the pianist played an arpeggio and a voice came zooming out of a half-pint gamin like the great locomotive chase. It roared up the trestle splashing its decibels against the walls, and I surrendered. I was surrounded. The voice had its own stereophonic sound.

Elmer Ogawa—a photojournalist who documented Seattle’s nightlife scene between the late-1940s and the early-1960s, and passed away in 1970—also began turning up at The Colony with his camera to see Suzuki perform at the crowded club. His photographs show the two-story supper club as the nightlife hub that it was. Women dressed in sleek and shiny sleeveless gowns, their dates as impressively attired in tuxedos or fine suits and ties. Rows of tables topped with white cloths, sparkling drink glasses, tall wine bottles, and ashtrays. Many tables lined the wraparound balcony overhead where supper club diners leaned over the railing to watch the dancers on the floor below as Suzuki effortlessly beguiled her audience with the latest jazz standard.

“It’s been awhile, but I can see [Elmer’s] face so clearly,” said Suzuki, who was eighty-two years old, retired, and living in Manhattan when I spoke with her by telephone in April of 2013. Suzuki recalled many photographers and press people visiting the club, but Ogawa was different. Although he was in his early fifties at the time, some thirty years older than Suzuki, he seamlessly meshed with a free-spirited band of characters and night owls that included a police detective, a former boxing manager, an advertising executive, and newspaper reporters and columnists. Suzuki fondly remembers joining them on trips to Von’s Cafe, a twenty-four-hour diner on Fourth Avenue downtown, for drinks, or for late-night, post-show dinners at 3:00 a.m. in Chinatown.

Nobody in that clan of late-night revelers talked about families or careers or anything serious. Suzuki was just out of college and living what she described as a magical, bohemian lifestyle in Seattle. “Oh, God, I miss that town,” she told me. “It was the easiest of times, you know. I didn’t have any responsibilities.”

As for Ogawa, Suzuki recalled, “I loved Elmer’s droll humor and easy company. Elmer was this floating persona that came in and out of my life. I never took anything quite seriously. You don’t when you’re in your twenties, I think. Elmer was just a very comfortable guy to me. He was a good fella. He was easy to be with. He was the nicest of people. He was friendly. He didn’t interfere. He didn’t project himself that hard.”

Ogawa was fond of Suzuki, and followed her career even after she moved from Seattle to New York City. In the decade or so after Suzuki left Seattle, she appeared on Broadway as the brassy nightclub singer Linda Low in the Rodgers and Hammerstein original musical “Flower Drum Song.” She was a guest on television shows hosted by Ed Sullivan, Jack Paar, Mike Douglas, and Red Skelton, and recorded four albums, one of which earned her a Grammy Award nomination. She appeared on the cover of Time magazine in 1958.

When I spoke with Suzuki by telephone, I mentioned the University of Washington recently uploaded to the Internet four of Ogawa’s photographs of her performing at The Colony. Suzuki responded, “What was I wearing? I only had a couple outfits at the time.” I sent her an e-mail with links to the photographs. One photograph showed Suzuki in a long dress and heels rehearsing with the tall, thin, bespectacled Bobrow, and a young man with curly blond hair, a black beret, and striped sweater who she immediately recognized as “Rocky.” “I was so chubby,” she chuckled.

Another Ogawa photograph showed her dancing alone onstage in front of a cluster of bongo drums, a piano, and an upright bass leaned against a back wall. Suzuki is wearing a long gray, frilly dress cut angularly low across her chest. Her arms are covered in long white satin gloves, and a pearl necklace loops around her neck. A white feathered hat is perched on her head and her mouth is wide-open in a silly pose of faux shock. “Oh, my God!” she cried. “You know, I don’t remember these dresses at all. I do not remember that dress. This is hilarious!”

Another photo has her dressed in a khaki trench coat, white sneakers, and a fedora, with Rocky and Bobrow in zoot suits. Suzuki: “Oh, what a goof! It’s us doing Guys and Dolls!”

Finally, she landed on the best photograph of the bunch. “I’ve seen this one,” Suzuki told me coolly. It’s showtime at The Colony, and Suzuki—wearing a long dress with short sleeves, crisp and stylish around her tiny frame—is alone at center stage. Her hair is pulled back in what television audiences nationwide would later recognize as her trademark long black pony tail, and her arms are outstretched, midsong, her eyes pointed toward an unseen audience. Off to her right, well-dressed men gather around tables draped in white cloth. One striking man in particular sits with his legs crossed, eyes fixed on Suzuki, and smiling wide as she expertly nails what appears to be a long and high note. He enjoys the show more than anyone else.

“Thank you for this,” she told me, as she finished looking at the photographs. She paused for a moment as I imagined her reflecting on her brief career in Seattle at The Colony. “No kidding. Well, there it is.

“It isn’t easy to remember about my long ago Elmer, other than seeing his face now clearly,” she added. “He had a great face. I remember his personality. I loved his droll humor and easy company. It was lovely! Seattle was the sweetest of times, I promise you, and it’s the last time I remember a loyal and close community of such characters!”

OGAWA’S PHOTOGRAPHS AT The Colony were evidence of Seattle’s well-dressed, connected, and cultured nightlife scene. But there was another side to Seattle’s nightlife that most people at The Colony probably never dared to experience. Most people, that is, except for Ogawa.

During most of the 1950s, Ogawa could be found at one of three places—working as a pipe fitter or boilermaker at one of the plants in South Seattle, on assignment for one of the Asian American newspapers or magazines, or, finally, in one of Seattle’s neighborhood dive bars.

Ogawa captured the gritty and blue-collar character of Seattle’s taverns. The still, black-and-white photographs are deceivingly rich. You swear your nose is tickled by a pungent, hoppy aroma. Frozen trails of cigarette-smoke-curls make you instinctively wipe your watery eyes. You can almost hear blues or jazz music blaring from a corner jukebox. Is that the warm clink of glasses as bleary-eyed and tipsy sots find yet one more reason to raise another pint of amber ale? His tavern photographs range from the festive (friends warmly celebrating birthdays, New Years’ Eves, and countless happy hours beneath a cigarette haze and harsh lighting) to the odd (Seattle cops elbow to elbow with barflies, all perched at long wooden bars, or African Americans seated warmly next to white patrons at a time when that wasn’t allowed in most parts of Seattle or the rest of the nation) to the occasional brawl (an old man, fedora precariously perched on his head, grabbing the throat of another man as they square off beneath a glowing sign for Olympia Beer) to the inevitable conclusion of someone passed out on a sidewalk at three in the morning.

At first, it’s difficult to reconcile Ogawa’s work as a credentialed photographer for that era’s leading ethnic media with his almost double life photographing Seattle’s rowdy bar scenes. Yet, one could argue the tavern photographs say more about the real Seattle during the 1950s than those scripted, well-orchestrated, ceremonial photos of politicians, beauty queens, and parade grand marshals that filled the pages of the Northwest Times and SCENE.

Even with his six-pound Crown Graphic 4×5 camera, popular among newspaper photographers, and conspicuous with its wooden frame, stainless steel case, leather strap, hood, and a shiny lens plate attached to a crinkled, accordion-like neck that jutted outward, Ogawa wasn’t intruding on some secret society of misfits and alcoholics. Ogawa was one of those misfits and alcoholics. If you accepted Ogawa, you accepted his camera too. It was a rule that many tavern owners welcomed. In the backgrounds of most of his photographs, Ogawa’s black-and-white glossy prints of drunken revelers can be seen crudely taped to the tavern walls.

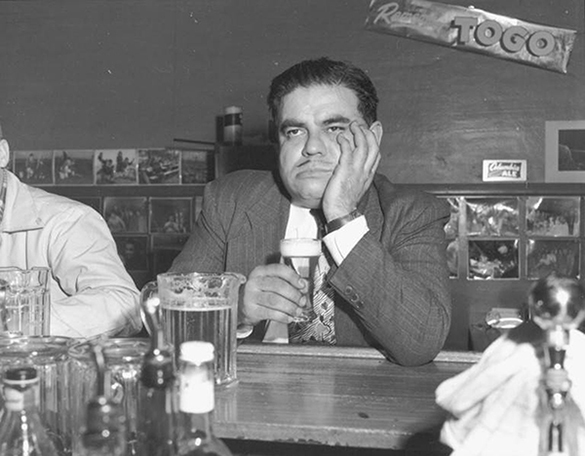

Ogawa proved to be just as interesting as his photographs. In one photograph, Ogawa, chomping on a cigar, is joined at the bar by two white police officers in crisp black uniforms, a slightly tipsy African American couple, and a brunette barmaid (a cord runs from the camera to Ogawa’s right hand, where he has remotely clicked on the shutter). In another photograph, taken at Tim’s Tavern in 1952, Ogawa appears to have had a rough day (or he’s mugging for the camera; it’s hard to tell, as Ogawa was a ham). He sports a pinstriped suit and dour frown as he holds a schooner of pale ale and stares off in the distance, an entire pitcher of beer resting on the bar in front of him. One more photograph shows what appears to be Ogawa, completely blotto, on New Year’s Eve—he’s at the bar, wearing a cheap foil crown, and sharing a raucous laugh with an old Caucasian woman who is about to blow into a paper party favor. In front of him is an oversized goblet of beer (it’s comically larger than any pitcher). A similar goblet appears in another tavern photo, this time with Ogawa staring longingly into it. A plaque on the side of the glass reads “BET YOU CAN’T” (drink the whole thing, it’s assumed).

Flipping through Ogawa’s tavern photographs is like a virtual pub crawl. At the Maynard Cafe, Ogawa photographed the action, as a group of people peered over a man’s shoulder, his tattooed arm following through after releasing a shuffleboard puck. In another photograph, a bartender in suspenders takes a break, his apron still tied and folded down at the waist, to play shuffleboard as a woman in a light floral print dress, her purse dangling off one arm, follows the puck.

Ogawa was also familiar with the bartenders who poured beers and mixed cocktails at the Banquet Tavern, a bar near the corner of Twelfth Avenue South and South Jackson Street, where the eastern border of Chinatown merged with a neighborhood that consisted mostly of African Americans. The Banquet Tavern looked like most bars at the time—a Bally’s Lexington pinball machine in one corner; signs for Rainier, Olympia, Budweiser, and Heidelberg beers; and packs of cigarettes stacked and for sale behind the bar, right next to a bulky cash register. But it also included scores of Ogawa’s photographs taped to the walls throughout the tavern, proof that he was a regular, welcomed customer.

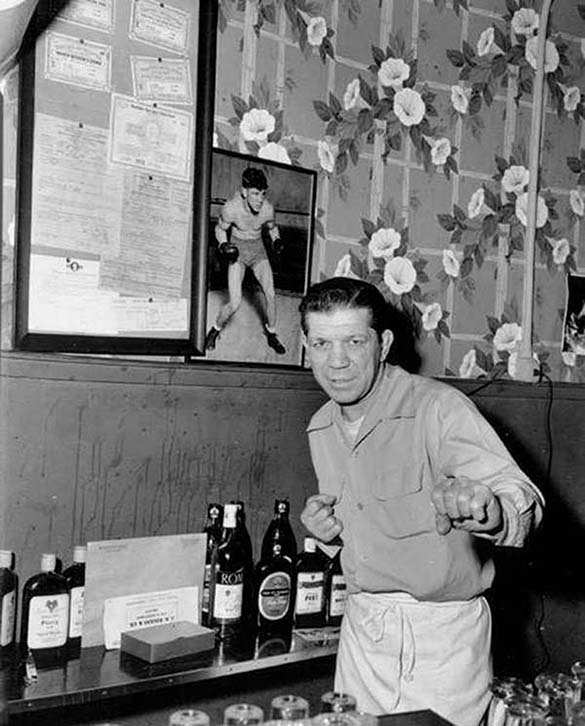

Ogawa clicked the shutter on his camera as a black man with thick, shaggy sideburns and mustache posed on the sidewalk. “BANQUET TAVERN” is painted on the windowpane behind him, and he’s holding a porcelain statue that includes a stein of beer resting on a wide base that reads “HAVE A HEIDELBERG.” In one print, the bartender—a fit, older man with a flat nose, greased black hair combed straight back, and a loose button-down long-sleeved shirt with a wide collar and an apron—strikes a boxing pose, crouching slightly with his fists clenched. He is standing in front of a framed photo of himself in his earlier years as a shirtless, toned young man and sporting tight shorts, boxing gloves, and tightly laced boots. In another photograph, the same man is at the end of a long wooden bar, head whipped back, hat barely on his head, chugging a glistening schooner of beer. One picture shows an Asian American bartender serving ten people lined up side by side at the tavern’s L-shaped bar—three African American men, one African American woman, three Caucasian women, and three Caucasian men. Everyone smiles beneath a neon Budweiser sign as they freeze to pose for Ogawa’s camera. It’s a similar milieu in other photographs, where blacks, whites, and Asians crowd into small booths to drain fat bottles of Rainier Beer and tap out cigarettes into overflowing ashtrays.

A few blocks west of Chinatown and farther along Jackson Street, in Seattle’s historic Pioneer Square neighborhood, Ogawa could be spotted at Our House Tavern, where he photographed what appears to be members of the Salvation Army—including a man in all black clothing, hat in hand—explaining their services to a group of midday tavern regulars standing outside on the sidewalk. At the Occidental Tavern Cafe, he photographed two dozen rattily attired men—perhaps homeless or unemployed—sitting under a blazing sun on the curb, the bar’s prominent neon sign hanging above the tavern’s front door. At the Klondyke Cafe, he snapped a late-night photograph of a heavyset woman in a flower-print dress, a wool coat perhaps a size too small, and white midrise heels singing and playing the banjo to a group of men dressed in suits and fedoras, gathered on the sidewalk outside and looking impossibly bored by her performance.

Ogawa’s best tavern photos in this neighborhood were taken at the Bohemian Club Tavern, located in the heart of Pioneer Square, near the corner of First Avenue and Yesler Way. His photographs show a comfortable, casual neighborhood bar festooned with signs advertising “roasted and toasted” sandwiches, pizza, hot dogs, beefburgers, barbecue, and Rainier and Olympia beers. One photograph shows a large, jolly woman with curly blond hair, her face painted heavily with makeup and lipstick smeared thickly around her mouth, as she uses a meaty fist to pull the handle on a tap and pour a pint of beer. Another picture shows a young man with black locks twisting out from beneath the brim of a cowboy hat precariously perched atop his head. He’s seated at the bar and firing a toy gun off in the distance. In another photo, Ogawa gathered five men for a group portrait in front of the club’s curly-scripted neon sign. One old man is hunched over and clutching his cane. Another is tall and heavyset, his belly just slightly poking out from the bottom of his short-sleeved button-down shirt. Another man pinches a cigarette between his lips as he smiles for the camera.

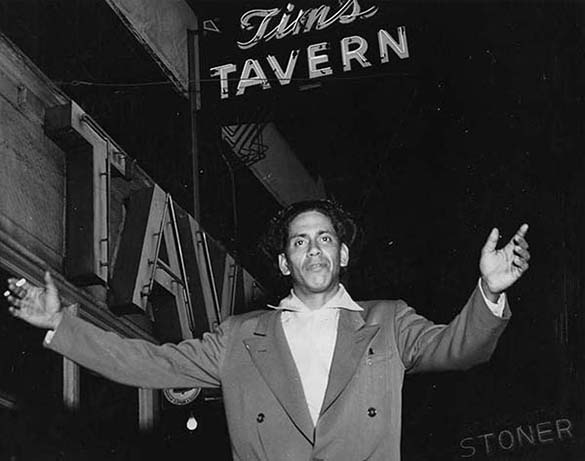

Ogawa could also be found in the bars east of downtown, in a neighborhood known as Capitol Hill. His photographs seem to show that Ogawa’s favorite place to drink in this part of town was Tim’s Tavern, near the crest of the long and steeply sloped Pike Street. In one snapshot, an African American man in a crisp white shirt and oversized double-breasted suit jacket poses beneath a neon sign announcing TIM’s TAVERN, his arms outstretched like an enthusiastic preacher, a cigarette smoldering in his right hand. Finally, another impression, taken in 1952, shows a beautiful blonde dressed stylishly in a long skirt and sleeveless white blouse perched on a bar stool. She clutches a fish-bowl-sized stein of beer and brings it to her lips as her dark eyes fetchingly peer over the rim.

Elmer loved beer so much, he once wrote an article (arguably a paean) defending Seattle’s taverns and their regular customers. “There Is A Tavern In Town” was published in the Northwest Times under the byline Elmer “Burp” Ogawa:

Anyone who has ever parked himself in a tavern, and is thus in position to be on the inside looking out, has opportunity to observe various little things which no doubt happen at any tavern or in any community. Take for example the good burghers of the tight little community who pass by and peer in the window. Slowly, slowly they traverse the full length of the front window, and when the further edge is reached, some are in danger of losing their balance from leaning backward. Sometimes, we’re in a mood to shout, “Come in, come in, you’re welcome to look around!”

Ogawa goes on to describe some of the bar regulars whom he considers friends—an amateur chef named Jim, who liked to cook fried angle worms sautéed in butter, olive oil, garlic, onions, lemon, and paprika; a wino and World War I veteran named “Shoofish,” who scraped together a living by running errands for the neighborhood dry cleaners, drugstore, and pool hall; and Katie, a “slender sprightly little gal who is frequently cute as a bug in a rug, and never looks or acts as old as we suspect,” who stops by the neighborhood bar on her way home from working at a laundry for a stiff drink (Ogawa added cheekily, “Almost forgot to mention the reason for mentioning Katie in this piece. She wears falsies made of crumpled up newspapers. Could we be facetious and call Katie a newspaper woman?”).

Ogawa’s article ends with a toast of sorts to his friends: Perhaps this is enough to make the ‘peering in window’ types who are maybe thinking only of depravity realize that so many of our friends are interesting imaginative people and we love them all.

Todd Matthews is editor of the Tacoma Daily Index, an award-winning journalist, and the author of several books. His journalism is collected online at wahmee.com.