TUESDAY AFTERNOON IN Tacoma’s Whitman neighborhood, and Pat McGregor and David Stafursky walk along South M Street, near South 38th Street, pointing out some of the area’s simple charms.

They stop beneath a massive maple tree, outsized and overgrown, craggy limbs stretching over the street. Seven years ago, its roots had buckled and cracked the sidewalks; neighbors elected to lower and modify the walkway instead of chopping down the tree, and the old maple continues to thrive. A few blocks away, at the corner of South 43rd Street and South L Street, the pair stops outside a former firehouse, Engine No. 8; its slanted, A-shaped roof, brick walls, and large windows now serve as a residence. Across the street, McGregor points to St. Paul United Methodist Church — a quaint, blue-and-white structure built in 1925 — where church services are still advertised on an old reader board. Glimpses of Mt. Rainier loom in the distance between rows of century-old Craftsman homes, bungalows, and small cottages, the mountain’s ridges creased with snow.

It is the older homes that most appeal to McGregor and Stafursky. McGregor lives in a Craftsman built in 1924, located across the street from Whitman Elementary School. The comfortable, one-story cottage is complete with a cat in the window and a couple campaign signs spiked in the front lawn. In contrast, Stafursky’s home, also a Craftsman, sits just around the corner. Built in 1911, it was the rectory for Tacoma’s first Polish American church.

“We’ve got some really historic homes in this area,” says McGregor as he walks his neighborhood’s tree-lined streets.

It’s a modest understatement.

According to Pierce County assessor’s records, 50 residential homes in the area, bordered by South 38th Street and South 43rd Street, and South M Street and South Thompson Street, date back 100 years or more. This year, nine more homes will turn 100. As a result, the pair has recently started a campaign to seek historic district designation for their neighborhood. McGregor was at City Hall last month to pitch the idea to members of City Council’s neighborhoods and housing committee. If successful, it could be a signal for other neighborhoods — a handful in South Tacoma, and the so-called “wedge” area near Wright Park and Multicare Health Systems — whose residents have considered historic district designation as a way to preserve the character of their area and thwart encroaching development.

It would also be no small victory for McGregor, 36, a teacher at Chief Leschi Elementary School, and Stafursky, 40, a service representative for Clearwire. In Tacoma, where the idea of historic preservation has at times lost out to the whims of developers, the number of historic districts is small. Only five historic districts exist in Tacoma. Three are listed on the local Tacoma Register (Old City Hall, Union Depot / Warehouse, and North Slope); four are listed on the National Register (Old City Hall, Union Depot / Warehouse, North Slope, and Stadium / Seminary); and four are listed on the Washington Heritage Register (Old City Hall, Union Depot / Warehouse, North Slope, and Salmon Beach).

In Tacoma, neighborhoods receive district designation and are placed on the city’s register through a nomination process. According to the City of Tacoma’s historic preservation Web site, once the Landmarks Preservation Commission approves the nomination, it then moves along to the Planning Commission, which may recommend to City Council creation of a new historic district. Technically, the district designation overlays existing zoning regulations.

Earlier efforts to grow the city’s register run from success and expansion in one part of town, to rejection seven years ago from property owners and City Council in another.

For McGregor and Stafursky, the goal is simple: improve neighborhood livability, honor the area’s rich history, and hopefully prevent developers from demolishing many of the old structures that give their neighborhood its distinctive character.

“If you go to the other side of I-5,” says McGregor, “you’ll notice they’re clearing out and leveling all kinds of homes and putting in apartments. We want to keep the historic flavor of the neighborhood.”

WHAT’S SO HISTORICALLY significant about the Whitman area?

It’s not simply the 100-year-old homes. It’s the story behind those homes — namely, the birth of an immigrant community. To better answer that question, Stafursky fires up his laptop computer and rests it on a counter top in his kitchen. He’s in the middle of renovating his two-story Craftsman home, and just about the only finished space is the kitchen and adjacent bathroom. Appliances and construction equipment crowd the front room, and peeling wallpaper is visible everywhere. The laptop contains scanned images of news clips dating back to the 1890s. Stafursky first started to gather these articles after he noticed the unusual layout of his home, which he purchased in 2004. Some walls had been moved or demolished. A door was buried in one wall. The front door, which today faces the street, was added years after the home was originally built; the original door faced what is now a driveway between his home and a neighbor’s home. “That caused me to think, ‘Wait a minute. Why would the front door of my house face the neighbor’s house?'” he recalls. It was then that he started to dig into the history of his home and neighborhood. What he discovered was a large, square plot 120 feet deep (and including the homes of McGregor and a neighbor) that was once the site of St. Stanislaus Church — the first Polish-American Roman Catholic Church in Tacoma.

He clicks on a news clip from 1892 about Rev. Michael Fafara, who created the church that year, and lived in what is now Stafursky’s home. Another photograph depicts the church circa-1918: the congregation crowds beneath the steeple; in the far right corner, Stafursky’s home is visible. Over several decades, two pastors lived in his home.

“Was the president born here in the Whitman neighborhood or anything like that?” asks Stafursky. “No. But this was the first Polish neighborhood in Tacoma. It was a blue-collar neighborhood that supported all the lumber mills in town. It was a real working-class neighborhood.”

Another document depicts city planner’s layout of neighborhood homes. The map blooms with color; green spots depict 115-year-old homes, yellow spots represent 100-year-old homes. A bar graph representing the number of homes built since the 1890s bristles with spikes for years 1900, 1910, 1918, 1921, and 1925.

It all points to why he’s interested in seeking historic district designation.

“My thing is that the house that was directly behind me was a 1910 Craftsman,” says Stafursky. “Those people didn’t want to invest any money into it. What did they do? They leveled it and built this tract home. It’s the same thing across the street. They didn’t want to do anything with it, so they leveled it. I’m trying to stop that from happening. [In other areas], they’re wiping out neighborhoods and putting in condos. There’s nothing to stop a developer from coming in here, offering everybody $300,000 for their house, and leveling them.”

IT’S ONE THING to seek historic district designation.

It’s another thing to sell the idea.

Start talking about historic district designation for your neighborhood, and you will likely find as much opposition as support. Saving old buildings should be an easy idea to embrace. But the biggest argument against designation, say most preservationists, comes from homeowners who fear it will cripple their ability to modify their homes.

The concerns? That they won’t be able to paint their homes, add a deck, or even trim their foliage.

“I think that there are a lot of reasons why people get concerned about becoming a historic district,” says City of Tacoma Historic Preservation Officer Reuben McKnight. “Some are misconceptions, some are perfectly legitimate.” The biggest concern is what many people view as a hurdle to home improvement. The municipal code states that any modifications to the exteriors of homes must be presented to the city’s landmarks preservation commission for approval (interior modifications are exempt). For example, if a homeowner who resides in a historic district requests to replace older, double-pane windows with a modern and inexpensive vinyl set, the commission will deny that request.

Other concerns are rooted in misconception: once the neighborhood is designated a historic district, homeowners must work to restore their homes to their original state. This is not true. The designation applies only to any modifications after the designation is made.

Still, homeowner concerns are the top reasons why among the three historic districts on the city’s register, only one is a residential historic district (North Slope). It’s the reason why, in 1999, an effort to create a historic district in Old Town failed.

“There was so much opposition to it,” recalls Ron Karabaich, who owns Old Town Photo and led the effort to seek historic district designation. “Primarily the developers down here didn’t want it. The idea was kind of new to a lot of people, and they didn’t understand it.”

Karabaich, who has lived in Old Town for 34 years, recalls a process similar to what McGregor and Stafursky are currently embarking upon. He worked with a small group that went door-to-door to garner support for the designation. At City Hall, he conducted slide presentations for councilmembers, showing designation benefits for the Old Town neighborhood.

Tacoma historian Michael Sullivan knows this story well. He was the City’s historic preservation officer when Karabaich and others were trying to push for the designation. At the time, says Sullivan, Tacoma didn’t have any residential historic districts. After Karabaich and others spent a year on neighborhood surveys and completing the necessary documentation, the proposal received nomination from the city’s landmarks commission. The next step? City Council approval. Sullivan remembers that on the weekend before Council was to vote on the designation, two Old Town residents who heretofore hadn’t attended the community meetings suddenly appeared and opposed the idea. They distributed flyers throughout Old Town describing how homeowners wouldn’t be able to paint their houses or trim their foliage without commission approval. “There was all kinds of stuff that wasn’t accurate,” Sullivan says. “It just freaked people out. It happened, literally, the weekend before the City Council meeting. People were completely jolted by the tactic.”

The resolution was “strongly defeated” by City Council, according to Sullivan.

At that point, adds Karabaich, it was “too late to turn things around.”

“Residential historic districts are a whole different thing,” says Sullivan. “People’s homes are involved. There’s a certain level of sensitivity.”

McKnight concedes the designation does mean there are limitations. “If you live in a historic district, the whole point is to preserve buildings,” he says. “It makes it difficult to tear things down that should be preserved. And there are additional processes if you want to make changes. For some people, that is sort of an objectionable situation.”

But he argues those limitations are the very ingredients that improve property values and quality of life in historic districts.

One example: a study examining the economic benefits of historic preservation in Washington State, and released by the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation in November 2006. According to the study, prepared by Matt Dadswell at Tetra Tech EC, Inc., and William B. Beyers of the University of Washington’s Department of Geography, property values of single-family residential neighborhoods in four cities (Bellingham, Ellensburg, Spokane, and Tacoma) that received historic district designation “increased at a faster rate than they did for similar homes in comparable neighborhoods that [did] not have a historic designation.”

The designation also affords tax incentives to homeowners. The most popular program is the Federal Historic Rehabilitation Tax Credit (HRTC). According to the City’s historic preservation Web site, HRTC allows a one-time, 20 percent federal income tax credit for the costs associated with rehabilitation of historic buildings.

“[In historic districts,] you have to go a little further, and use better materials than normal building codes itself would require, and that can introduce some costs,” McKnight says. “But the benefit is that your neighborhood has a status, and part of being a historic district is that you have planning vision for your neighborhood. The other thing is that the state study was able to demonstrate that homes within historic districts have the same property value as homes not in districts, and gain value faster. It could be because regulations protect the district, people are attracted to these districts, and these districts attract a certain kind of homeowner.”

ACROSS TOWN, IN the North Slope Historic District, Marshall McClintock sets out on a walking tour of his neighborhood. “Every house has a story,” says McClintock, 55, who lives in a part of Tacoma that has mostly benefited most from its historic district designation.

He’s agreed to meet for a walking tour of his neighborhood, and we head up North Seventh Street toward an area that is home to what neighbors call ‘The 12 Apostles.’ McClintock is board chair of the North Slope Historic District, an area of town bounded by North I Street, Division Avenue, North Steele Street, and North Grant Avenue. For the past five years, he has lived with his partner, Geoff Corso, in the former home of the department store founder Henry Rhodes. Located at North Seventh Street and North J Street, the home is a neighborhood anchor: a two-and-half-story, 6,000-square-foot structure with coral blue shingles, white trim, and a long porch lined with columns. A white picket fence borders a gurgling fountain and sprawling garden.

Walking briskly through the North Slope, McClintock points out some of the more notable features among this neighborhood of Craftsman, Victorian, Colonial Revival, and Foursquare style houses: a yellow neo-classical home dating back to the 1890s, and once owned by Otto Richter, head of the state’s largest manufacturer of bicycle tires — Tacoma Rubber Company; another home has ties to a wealthy cigar manufacturer who owned a shop downtown; patches of cobblestone streets peek through the asphalt and date back to the days of horse-and-buggy.

This is the neighborhood that McGregor and Stafursky want the Whitman area to resemble. Though homes in both neighborhoods differ — the North Slope’s expansive homes served the city’s bank executives and civic leaders, while the Whitman area’s cottages and Craftsman homes served the blue-collar Polish American community — the result is what McGregor and Stafursky want: improved neighborhood livability and some level of protection against developers. To that end, McClintock has helped McGregor and Stafursky with advice on what the designation means, filling out applications, and collecting information to share with neighbors. He has even hosted walking tours much like the one today.

The circumstances that led to the creation of the North Slope Historic District are similar to the Whitman Area. Beginning in 1955, large homes were being demolished to make way for apartment complexes. Property owners had a hard time renting to people who expected more contemporary homes, and the city’s zoning code permitted the construction of new multi-family housing. “What else were you going to do with these big old homes except divide them into apartments or tear them down?” says McClintock. Couple that with an increase in neighborhood crime, and by the late-1980s, a small group of residents was searching for ways to get control of their neighborhood. They turned to the City’s historic preservation office.

“There were sort of two prongs,” explains McClintock. “There was this notion of historic preservation, and, ‘How do we keep this great neighborhood from being demolished?’ And there was also this issue of, ‘How do we save our neighborhood?'”

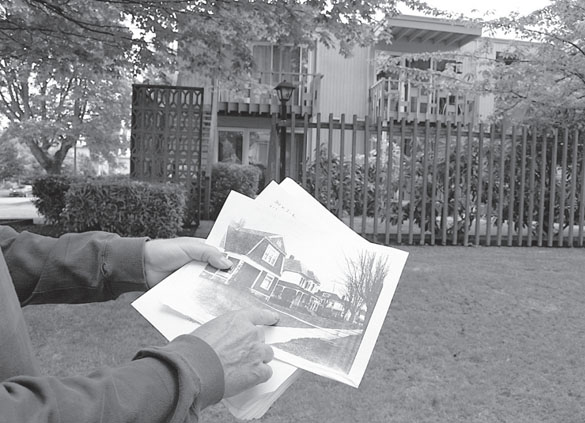

Evidence of this demolition exists during our walking tour. Sprinkled among the older homes are flat, angular, 1960s-style apartment buildings, and split-level ramblers. At one point, McClintock stops to compare a black-and-white photo of a row of 1900-era houses against what exists today: a 30-year-old, purple-gray, two-story terraced apartment building. A few moments later, outside the site of the so-called 12 Apostles, the contrast between what the North Slope area once was, and what residents tried to prevent through historic district designation, is clear. Two homes are left of a row of 12, 1890s-era, Queen Ann style homes designed by Architect William Bullard, and named for their clean and similar lines. The other 10 homes were cleared in the 1970s by HUD to create a massive block of senior housing.

The idea to create a historic district was unprecedented. Residents worked with the City’s historic preservation office to create a history of the neighborhood and prove to City Council that neighborhood support was behind the idea. In 1994, the North J Street Historic District was created with City Council approval. When neighbors on North I and North K Streets saw what happened, they asked for the same designation. In 1996, the district was expanded. Three years later, the district was expanded again to include an uphill southern section of North M Street and North Grant Street. Today, the North Slope is one of the largest neighborhood historic districts in the country, with more than 950 buildings.

McClintock says he is familiar with the concerns over historic designation. However, in the North Slope’s case, neighborhood support existed from the start, he says. One of the biggest hurdles was explaining it to city planners and City Council. Also, other neighborhoods argued that this historic designation was giving North Slope residents zoning privileges. “This was a new thing,” he explains. “Some people on City Council and within city government — and the city generally — were kind of like, ‘What is this thing? Are these people getting something we’re not getting?’ That’s one of the things we find humorous. Really, what we are doing is saying, ‘We’re willing to pay more money to maintain our homes than other folks in other neighborhoods.’ In some ways, that’s what a neighborhood district designation amounts to. Our houses have acquired higher value [because of the designation],” he adds. “It’s certainly reflected in our property taxes. We’ve improved the neighborhood and pay more taxes as a result. But people seem pleased to do that — or at least see the benefit of the improved neighborhood.”

MCGREGOR AND STAFURSKY are more than familiar with the concerns raised by property owners over historic district designation. In an ironic twist, Stafursky was initially one of those concerned property owners opposed to historic districts.

McGregor first thought of the idea after a presentation by McKnight at a South End Neighborhood Council meeting last fall. The City had recently worked with a consultant on a report to identify potential historic districts in South Tacoma. “I approached Reuben after the meeting and said we might be interested in this in the Whitman area,” says McGregor.

“I think when I first asked Dave if he wanted to work on the historic district, his first answer was no,” adds McGregor, grinning. “Even he was worried about it: ‘Are they going to tell me what to do with my house?'”

After researching the historic significance of his own house, Stafursky was onboard.

Recently, the pair has gone door-to-door explaining the plan to neighbors. They expect to spend a year networking with neighbors. If support exists, they will request a nomination. In the interim, the idea is a regular discussion topic at monthly Whitman Area neighborhood meetings.

“I’ve had a couple negative responses,” says McGregor. “I’ve had quite a few positives, too. And a majority of people are just uneducated on the issue, or unaware. We’ve got to have information and ammo because they’re going to have questions, and I want to have answers for them. Most folks have said, ‘OK, but what does a historic district designation mean?’ That’s been the question that’s hard to answer, unless you go to the North Slope, check out the homes, and see it for yourself.”

At one meeting, a resident told McGregor and Stafursky, “Look, I know somebody who lives up in the North Slope. They couldn’t put vinyl windows on their house, and it cost them $300 more per window to put in double-panes. But I’m for it. I already have my vinyl windows in, and you can’t make me take them out.”

As evidenced by Old Town’s failure and the North Slope’s success, the entire Whitman community will have to be onboard for the council to approve designation. “It’s really difficult to have a successful historic district if there isn’t ardent support from people who own property there,” says McKnight. “In the North Slope, it really was a process that originated from people that lived in the neighborhood — not the City. I think that’s key.”

McGregor and Stafursky say they understand this. They also welcome the challenge in educating neighbors on the benefits of historic district designation.

“One of the things we’re trying to point out is that we’re not trying to make it more expensive,” McGregor adds. “But how would you like it if all of a sudden they knocked down three houses next to you and put up apartments? That’s what was happening on the North Slope. To me, paying a little more for windows is a small price to pay in comparison.”

Todd Matthews is editor of the Tacoma Daily Index and recipient of an award for Outstanding Achievement in Media from the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation for his work covering historic preservation in Tacoma and Pierce County. He has earned four awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, including third-place honors for his feature article about the University of Washington’s Innocence Project; first-place honors for his feature article about Seattle’s bike messengers; third-place honors for his feature interview with Prison Legal News founder Paul Wright; and second-place honors for his feature article about whistle-blowers in Washington State. His work has also appeared in All About Jazz, City Arts Tacoma, Earshot Jazz, Homeland Security Today, Jazz Steps, Journal of the San Juans, Lynnwood-Mountlake Terrace Enterprise, Prison Legal News, Rain Taxi, Real Change, Seattle Business Monthly, Seattle magazine, Tablet, Washington CEO, Washington Law & Politics, and Washington Free Press. He is a graduate of the University of Washington and holds a bachelor’s degree in communications. His journalism is collected online at wahmee.com.