In the spring of 1792, British Navy Captain George Vancouver was aboard the H.M.S. Discovery in Puget Sound and surveying the natural environment when he noticed a large, v-shaped notch in the foothills of Mount Rainier. Vancouver, whose ship was anchored at Restoration Point on the southern end of Bainbridge Island, was intrigued. What could lie within and beyond that carved and concave feature? A large river? The Northwest Passage?

He noted the feature in his journal—“The appearance of a very abrupt division in the snowy range of mountains immediately to the south of Mount Rainier, which was very conspicuous from the ship, and the main arm of the inlet appearing to stretch in that direction from the point we were then upon”—and boarded one of two smaller boats that headed south, past Vashon Island, and into Commencement Bay, only to find what he believed to be a dead end. Vancouver noted, “We were excessively anxious to ascertain the truth, of which we were not long held in suspense. We found the inlet to terminate here in an extensive circular compact bay, whose waters washed the base of mount Rainier.”

Vancouver would go on to name dozens of mountains, waterways, and islands in the Puget Sound area—but the v-shaped notch remained nameless and somewhat elusive.

That changed several years ago when a Puyallup resident named Barbara Reid started to explore Puget Sound in her own boat. Reid, 72, retired from the Army 30 years ago, bought a Swedish-made Albin 25 watercraft in 1999, and soon began to navigate the Columbia River, Snake River, and the route taken by Peter Puget (Vancouver’s lieutenant) as he explored Puget Sound. In total, she logged more than 8,500 nautical miles over 15 years before recently selling the vessel.

Three years ago, Reid was reading Vancouver’s journal when she came across his note about the v-shaped notch. She could see it, too. Reid’s observation set in motion a plan to name this feature Vancouver Notch. She shared her idea with local historical societies, museums, yacht clubs, and elected officials. Earlier this year, she submitted a 24-page application (with six letters off support) to the Washington State Department of Natural Resources to formally name Vancouver Notch.

“It is clear that the notch was visible from not only Restoration Point but the entrance to Commencement Bay, as well,” said Richard W. Blumenthal, an author who spent the past 15 years writing five books about local maritime history, including With Vancouver in Inland Washington Waters (McFarland & Co., Inc., 2007). “Vancouver’s chart also reflects the notch. From the quote [in his journal], Vancouver apparently guessed the inlet which they were exploring might turn eastward toward the notch. But his guess was soon dispelled when they entered Commencement Bay and found it closed.”

As for whether Vancouver thought the notch might lead to the Northwest Passage?

“Anything else Vancouver thought about this notch is subject to speculation,” said Blumenthal. “Although I don’t think it impossible that he might briefly have connected it to the Northwest Passage, I don’t know—and he didn’t provide any additional information in his journal.”

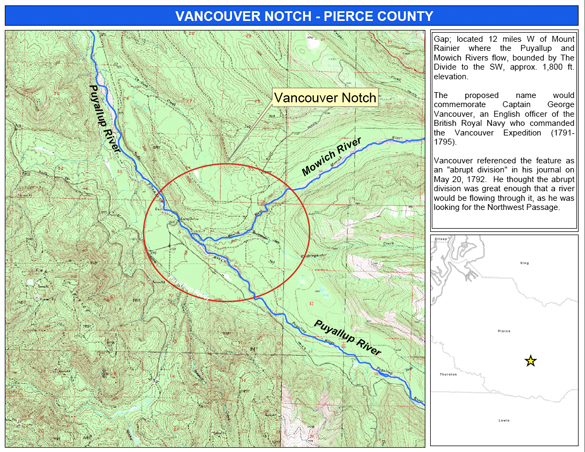

Today, the notch—located on privately owned land 12 miles west of Mount Rainier, where the Puyallup River and Mowich River intersect, and bounded by an 1,800-foot ridge known as “The Divide”—remains somewhat elusive. Vancouver didn’t explore it 223 years ago, and Reid, for all her interest in it, hasn’t visited the notch, either.

“You can’t. It’s very narrow and it’s a long way up there,” said Reid during an interview this week at her Puyallup home. “There is a dam on the Puyallup River that would prevent you from going all the way up. They are doing a lot of logging on private roads that are all closed off, so you can’t really get up there to, say, go above the dam, put a kayak in or some kind of row boat, and go up it.”

Reid’s dining room table was covered in nautical charts, maps, and photographs of the area. At one point, she opened a laptop computer and zoomed in on the area using Google Earth—soaring over forested hillsides, skimming the area where the Puyallup River and the Mowich River intersect, and tracing logging roads that weave through the area.

For now, the Washington State Committee on Geographic Names is accepting public input on Reid’s proposal before it votes on the issue in October. If the proposal is approved, it will eventually bump up to the federal level and the United States Board on Geographic names. In the end, the name Vancouver Notch will be entered into a database maintained by the U.S. Geological Survey and used by most cartographers to create maps.

“You really want to get in the database,” said Caleb A. Maki at the Washington State Department of Natural Resources. “Responsible cartographers pull the names from that database.” Maki said Reid submitted a strong application. “I thought it was prepared well. She didn’t have to send additional information or anything. I didn’t have to follow up. She had all of the pertinent details.”

Blumenthal, the historian and writer, would like to see the name approved.

“I fully support Barbara’s application,” he said. “Notch is a very descriptive term and to have something in our local area (ignoring Vancouver Island, Vancouver, B.C. and Vancouver, Wash.) named for George Vancouver is appropriate.

“This recommendation [to name Vancouver Notch] is entirely her effort,” he added. “I simply provided some limited moral support as I thought—and still do—that her application was more than appropriate to honor the gentleman who discovered and charted our inland waters.”

The Tacoma Daily Index discussed the proposal at length with Reid this week. Our interview has been edited for clarity and condensed for publication.

TACOMA DAILY INDEX: How did this idea come about to name a section of the Mount Rainier foothills after Captain George Vancouver?

BARBARA REID: After I replicated [Lieutenant Peter] Puget’s route, I really got interested in trying to find out about [Captain George] Vancouver’s route and whether he actually came down the Sound. I discovered Richard Blumenthal’s book, which actually states very clearly right out of Vancouver’s log where he actually went.

[Vancouver and Puget] arrived at Restoration Point on Bainbridge Island on the 19th of May. The next morning, Puget takes off to explore. [Captain George] Vancouver is sitting there [aboard] the Discovery, anchored. He can see—and he describes in his journal very clearly—this abrupt, geological formation, thinking that it could be the entrance to the Northwest Passage because it was such an abrupt division in the southern slope that a river would have had to have cut thought that.

So I read this and I think, “Oh, my gosh. If he can see it, I should be able to see it.” So I went out on my boat and there it was. I thought, “Oh, I’ve seen that before.” I never paid any attention to it. Everybody wants to see Mount Rainier. They don’t pay attention to the foothills. I thought, “I wonder what river that is.” I asked around to all the park rangers that have lived here their whole life. They didn’t know. I went on Google Earth and saw that it was the Puyallup [River]. I was thinking that it might be the Nisqually [River] because the Nisqually [River] is bigger. I ran into Richard Blumenthal at a presentation that he was doing and he said, “I know how to get things officially named.” That’s where it started. That was the seed that was planted.

INDEX: When Vancouver came down to Commencement Bay to explore the notch, what did he find? Did he ever sail up the river to explore the notch?

REID: No. He just went into Commencement Bay. He was anticipating that there would be this big river coming down that would connect into the bay. They were all in search of the Northwest Passage. It would be financially very great for any captain to find it, so that’s what the whole purpose of the whole expedition was. Here he’s looking at this v-shaped notch, and he’s got the wherewithal to think that a river is flowing through there and it’s significant enough of an abrupt division. It just didn’t go to England [laughing].

Everything ended in mud flats and deltas so they continued back north. He described [the area] as a “compact bay.” There’s just a big delta that goes way back. You don’t really see any of these individual rivers coming down because they are spread out way back into a delta system. So you don’t see [the rivers] at all. Even today, you don’t know that the Puyallup River is right there. You wouldn’t know it until you got up into it.

He knew there was a river, but it wasn’t the Northwest Passage. If he got over there and he could see something as wide as the Strait of Juan de Fuca, you bet he would have headed up there.

INDEX: Did you get in your boat and go up the Puyallup River to see the notch?

REID: No. You can’t. It’s very narrow and it’s a long way up there. There is a dam on the Puyallup River that would prevent you from going all the way up. They are doing a lot of logging on private roads that are all closed off, so you can’t really get up there to, say, go above the dam, put a kayak in or some kind of row boat, and go up it.

I wanted to get somebody to fly me up there. I almost had something secured, and then there were problems with that and it didn’t go through. I just haven’t found a pilot.

I’ve been as close as I can by car. If you go up the Mowich River Road to the Mowich River Lake, I got there and the pictures that I took, I could see way down. I mean, it’s like thousands of feet down. Very steep to get down. I think what I was seeing was the Mowich River. I was looking at this ridge here. Way, way down I could see this sliver which I thought was the Puyallup River.

I think it’s do-able, but it would be extreme. You could hike it if you got permission from the logging company to hike down to it. At that point, it will be a fairly little expanse of water. If you had a little inflatable that you could take with you, then you could run that down to the dam. That’s for younger people than me (EDITOR’S NOTE: Reid and the Tacoma Daily Index visited the site in October. Click here to read our feature article about the trip).

INDEX: When you look toward Mount Rainier today, do you even see the mountain anymore? Or do you just see the notch?

REID: I see all of it. But when you are looking at the weather cams in the morning on the TV stations, you can see the notch on a clear day. It’s just right there.

INDEX: Why is it so important to name Vancouver Notch?

REID: I’ve got to do this because Vancouver named a lot of things. Here we are, 223 years have gone by, and nobody really pays any attention to it. It’s really worth the effort to get this named to honor him. He was so insightful that a river was flowing through there and it could be something. I think it’s important. It’s part of the landscape that we see everyday. And just to honor Vancouver, that is a significant thing. It’s just bringing this obscure little couple of paragraphs in Vancouver’s journal and connecting the dots. I think it’s really important to shed light on. My friends say, “You have too much time on your hands that you are reading Vancouver’s log.” I never would have dreamed that I would be naming something on a mountain.

!["It's really worth the effort to get this named to honor [Captain George Vancouver]," said Puyallup resident Barbara Reid. She has submitted an application to name a feature of the Mount Rainier foothills Vancouver Notch in honor of the late explorer. "I think it's important. It's part of the landscape that we see everyday.I think it's really important to shed light on." (PHOTO BY TODD MATTHEWS)](http://spiidx.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/080315_vancouver_notch_f_web.jpg)

!["It's really worth the effort to get this named to honor [Captain George Vancouver]," said Puyallup resident Barbara Reid. She has submitted an application to name a feature of the Mount Rainier foothills Vancouver Notch in honor of the late explorer. "I think it's important. It's part of the landscape that we see everyday.I think it's really important to shed light on." (PHOTO BY TODD MATTHEWS)](http://spiidx.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/080315_vancouver_notch_f_web.jpg)

- Tacoma Daily Index Top Stories — October 2015 (Tacoma Daily Index, Nov. 2, 2015)

- Vancouver Notch: Committee approves proposal to name Mount Rainier foothills feature (Tacoma Daily Index, Oct. 26, 2015)

- Vancouver Notch: In Mount Rainier’s foothills, Barbara Reid completes one famous explorer’s journey (Tacoma Daily Index, Oct. 21, 2015)

- Vancouver Notch: Committee to consider proposal to name Mount Rainier foothills feature (Tacoma Daily Index, Oct. 19, 2015)

- Tacoma Daily Index Top Stories — August 2015 (Tacoma Daily Index, Sept. 1, 2015)

- Vancouver Notch: Mount Rainier foothills could soon honor the late explorer (Tacoma Daily Index, July 31, 2015)

Todd Matthews is editor of the Tacoma Daily Index, an award-winning journalist, and the author of several books. His journalism is collected online at wahmee.com.