EDITOR’S NOTE: This article is excerpted from Elmer Ogawa: After hours with Seattle’s forgotten photographer, a biography written by Tacoma Daily Index editor Todd Matthews. This is the final installment of three parts that began on Mon., Dec. 7, continued on Weds., Dec. 9, and concludes today. More information is available online at wahmee.com.

ELMER OGAWA’S SEATTLE doesn’t exist anymore.

The taverns and dive bars Ogawa frequented and photographed are long gone. It’s the same story for the mom-and-pop laundries, jewelers, ice cream stands, and appliance shops that Ogawa—a freelance photojournalist who was most active between the late-1940s and the early-1960s, but passed away in 1970 at age 65—photographed as a way for newspapers and magazines, such as the Northwest Times, SCENE: The Pictorial Magazine, and Pacific Citizen to tell the stories of Seattle’s hardworking Asian American community. Much the same way that it is difficult to find Ogawa’s friends and cohorts still alive today, many of his former haunts have also disappeared.

Tim’s Tavern on Pike Street is now a gourmet cupcake shop located on the ground floor of a very modern and sophisticated condominium building. The Klondyke Cafe in Pioneer Square is now a parking lot. The building that was once home to Barney’s Cafe near the corner of Seventh Avenue and Pine Street in downtown Seattle was razed long ago, replaced by a massive city-block-sized building that includes a Hyatt Hotel, Starbucks, Cheesecake Factory, and parking garage. Perhaps Ogawa would recognize the former home of the Bamboo Inn Cafe in Chinatown. Although it looks completely different today, the address is now home to Bush Garden, a sukiyaki restaurant with a bar popular among Seattle’s karaoke crowd.

Ogawa was buried at Resthaven Memorial Cemetery. The cemetery’s history dates back to 1884. Perhaps most notably, it’s where Seattle’s first and only female mayor, Bertha Knight Landes, was buried in 1943. More than forty years after his death, I visited Ogawa’s grave on a warm spring afternoon. I drove through the cemetery and toward the property’s eastern boundary past a squat and weathered marble mausoleum that was built for the late and prominent attorney and judge Thomas Burke, who opposed an anti-Chinese movement in Seattle during the late 1880s and later started a railroad company. Around the sloped hillside of Veterans Memorial Cemetery, the grave sites are dotted with pristine white marble headstones and a couple imposing cannons from “Old Ironsides” sit nearby. I drove along a narrow access road that winds between towering and lushly green poplar trees and parked at the foot of a row of graves and headstones where Ogawa is buried. After a short walk over soft grass, some ten rows in from the road, I stopped at Ogawa’s grave. Atop a thin, flat slab of granite, the following was inscribed on a sturdy bronze plate: † ELMER OGAWA WASHINGTON SGT CO D 58 INFANTRY WORLD WAR II NOV 9 1905 – JULY 1 1970.

But Ogawa’s legacy isn’t buried beneath that tombstone. His legacy is captured in the more than ten thousand photographs his brother donated to the University of Washington more than forty years ago. Whether that legacy ever becomes part of the narrative history of Seattle remains to be seen. Most people have never heard of Elmer Ogawa. His contemporaries have passed away, and his photographs have been stored in a basement at the University of Washington—overlooked, untouched, and ignored.

One person who knows Ogawa’s photographs well is Nicolette Bromberg, the visual materials curator at the University of Washington Libraries Special Collections. Bromberg has worked as a photographic historian and archivist for nearly thirty years. Before she was hired at the University of Washington in 2000, she was the visual materials curator at the Wisconsin Historical Society, as well as the photo archivist for the Kansas Collection at the University of Kansas. She has co-authored two books on Pacific Northwest history, including one about a group of Japanese immigrant photographers who founded a camera club during the 1920s and went on to earn national attention for documenting the natural beauty of the Pacific Northwest.

One afternoon, I meet Bromberg in the main research room at the University of Washington Libraries Special Collections. Bromberg appears every bit the archetypal historian and curator—a small woman in her sixties with curly grayish-brown hair and reading glasses—and has an almost giddy enthusiasm for helping visitors navigate the library’s vast collection.

Bromberg has been fond of Ogawa ever since a colleague pointed her toward his work shortly after she first arrived at the University of Washington. She pulls up the photographs that have been digitized so far, and starts clicking through a collection of Ogawa’s tavern photographs that have been uploaded to the UW Libraries Special Collection Web site.

“When he’s in the bars, he’s in there,” Bromberg says in low tones, so as not to disturb other library visitors. “You know, there’s two kinds of photography. There’s outside and inside. You’re either outside photographing the act of something. Or you’re photographing something from within. Elmer was always photographing from within.” Bromberg smiles as she thinks about Elmer tucking into a local tavern, setting his bulky camera on the bar, and ordering a cold pint of Rainier Beer. The bartender would pull pint after pint, and Elmer and his drinking buddies would kick back, tap cigarettes into ashtrays, and tell jokes and stories. At some point, Elmer would say, “Hey! Let me get a picture!” and everyone hollered, “Yeah!”

“Look at his photos,” Bromberg excitedly exhales, as she continues to click through the images. “They are participating. They aren’t scowling at him. Just looking at him, he must have been an effusive character. He must have just drawn people to him. Black, white, or Japanese—they’re all having a good time. And he’s having a good time. They’re relaxed. They’re not upset he’s taking photographs. Maybe he was charismatic. He probably got people going when they were drinking and having a good time. He could have been an actor!”

Bromberg pauses a moment before she clicks through more pictures. She lands on a series of self-portraits.

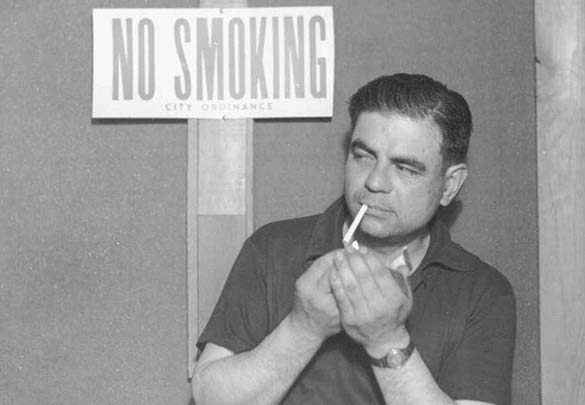

“I’ve always just loved his goofiness and quirkiness,” she says, giggling softly as she clicks on a photograph of Ogawa, who leans against a wall and prepares to light a cigarette with a NO SMOKING: CITY ORDINANCE sign hanging on the wall above him. It’s Ogawa channeling James Dean.

It’s not the only example of Ogawa turning the camera on himself. He appears in scores of his own photographs alongside fellow revelers—smoking cigars, chugging frosty pints of beer, and trying his luck at a game of dice—and just as gleefully intoxicated.

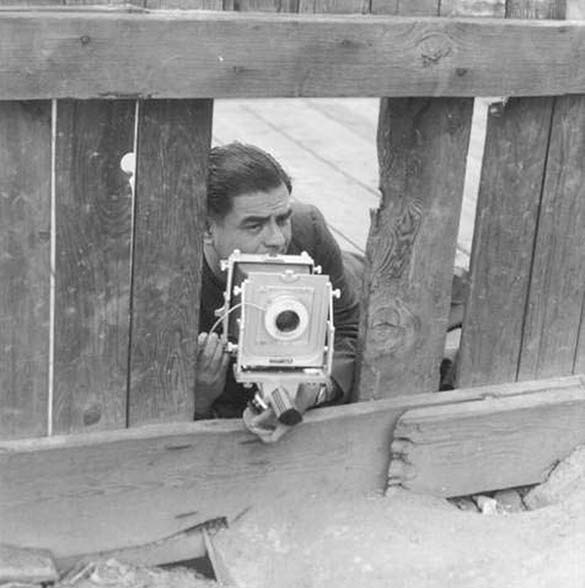

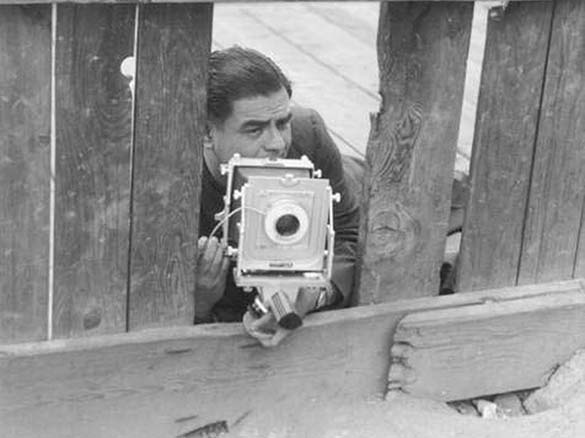

An interesting “Ogawa at Work” series of four photographs taken during the 1950s shows him working as a photographer. In one picture, Ogawa stands in an empty field in front of his bulky camera, which is mounted atop the sprawled legs of a tripod. A boxy suitcase that carries his equipment lies open on the field nearby. Ogawa, whose dark, rumpled suit covers his tubby frame, prepares to load film into the camera. In the next image, Ogawa is bent at the knees, a cigarette pressed between his lips, and peering from behind the camera to set up his next shot. In a third photograph, Ogawa lies on the ground—still dressed in his suit, his black hair still slicked back like the grooves on a record—and positions the camera between the broken slats of a wooden fence. Finally, the last shot shows him standing in front of a wall of frosted glass windowpanes in what appears to be a ground-floor studio or warehouse. Soft light pours through the windows as Ogawa—now comfortably dressed in a dark short-sleeved polo-style shirt and khaki slacks, a rolled-up newspaper poking out of his back pocket—holds up one of his glossy photographs for closer inspection. Clipped to a post behind him are nine prints of his most recent photographs.

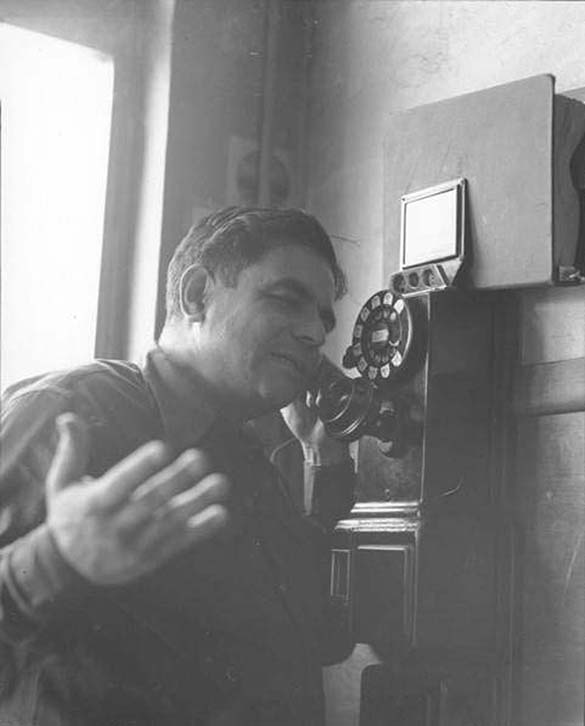

Bromberg continues to sift through Ogawa’s work, landing on more self-portraits. There is a studio-quality photo of Ogawa: clean-shaven, hair combed, and wearing a gray suit, gracefully leaning in toward the camera. Two 1956 prints show Ogawa dressed as some sort of private detective straight out of a pulp crime novel (fedora, heavy trench coat, neatly trimmed mustache) and holding a camera near his face as he waits for the next surreptitious shot. Another photograph presents Ogawa curled up on a sofa, dressed in dark pinstriped slacks and a long-sleeved dress shirt, presumably napping, yet holding a drink in his left hand. And, finally, a candid shot displays Ogawa in what appears to be an intense conversation at a pay phone at one of the local bars, waving his right hand, cupping the earpiece with his left hand, and speaking into the phone’s snoutlike microphone.

Typically, Ogawa made little effort to hide the fact that he was taking a picture of himself. There’s almost always a conspicuous cord snaking its way from the camera to one of Ogawa’s hands so that he can click the shutter. But that element is missing from most of these self-portraits. It’s not clear who the photographer was.

Most of Ogawa’s self-portraits as a photographer are refined and carefully crafted—attired in a clean suit, hair neatly combed, carefully setting up his next shot, and thoughtfully considering each photograph he developed. A 1952 self-portrait working his “day job” as a boilermaker in Seattle’s industrial yards was just as carefully composed. In one image, Ogawa appears sweaty and tired and grease stained, a clean white cigarette dangling between his lips. He wears grimy coveralls, a white T-shirt visible from behind the dirty fabric, and a small cap with an upturned visor. Beside him is a massive eight-ton, cast-iron metal shearing machine with a “CINCINNATI” logo stamped on its side. The machine is imposing and looks like it could do some real damage at the hands of an amateur. Indeed, a large, dented sign posted to the side of the machine reads, “See your foreman before shearing stainless or other alloys.”

Bromberg has studied photographs for decades, and written books and articles about some of the most prominent photographers in the United States. But I had a sense that there was something about Ogawa’s lack of artistic pedigree and abundance of DIY spirit that she appreciated in his work. It was almost like comparing a classical orchestra performing in the finest concert hall to a jazz trio ripping it up in the corner of a run-down coffee shop.

In spring of 2008, the University of Washington Libraries devoted a page of its quarterly newsletter to announce a call for donations. “Your help is needed to preserve a collection of unique photographs documenting Seattle life and communities,” read the announcement, which included two classic, warm Ogawa photographs: five Caucasian and Asian American teenagers wearing blazers, collared shirts, and khaki pants, hoisting a youth league football trophy during a banquet dinner in 1954; and a Japanese American man, Joe Nam Kun, posing with his wife and two daughters in their Seattle living room in December 1952. “Many of [Elmer] Ogawa’s negatives have vinegar syndrome, meaning that the negatives have buckled and the emulsions have begun to bubble and curl so they can no longer be printed. Please help to preserve Elmer Ogawa’s photographs. With your support, we can save this important collection documenting the individuals and communities who have helped to shape Seattle’s history.”

During my visit with Bromberg, I asked if any progress had been made to save his photographs. The only way she knows how to answer that question is to take me on a tour. Bromberg leads me away from the main research room and down a short and dimly lit hallway, where she swipes a key card and pushes open a heavy door to reveal a behind-the-scenes look at Special Collections—a room that appears to stretch out endlessly with islands of low desks piled high with archived boxes, binders, and computer terminals. We zigzag between desks for a bit before arriving at a far corner of the room in front of a cheap, aluminum-framed bookcase whose five shelves sag with the weight of Ogawa’s loosely boxed and uncategorized negatives. Some negatives are filed in small shoe-box-sized cases, the way a young boy might file his baseball cards. Other negatives consist of thirty-five-millimeter film loosely coiled on bulk-loaded rolls, like old movie reels, now barely protected by their dented and damaged tin cases.

In total, there are just over eleven thousand Ogawa negatives here; just over one thousand have been lost to acetate deterioration. “There’s probably more by now because they are going fast,” Bromberg tells me as she begins to open boxes and hold negatives up to a bank of overhead lights to check their images. “Here’s one of him in a bar, of course, holding a puppy,” she says, peering into the translucent film. The damaged negatives are bubbled and curled, and Bromberg encourages me to smell some of them for that sour, potent signature whiff of vinegar that gives this type of deterioration its namesake “vinegar syndrome.” The damage vinegar syndrome afflicts on film—cracking brittleness, buckling, shrinking, and bubbling—can’t be undone, and leaves negatives looking like blistered scales.

Beyond the physical damage, there is a fair amount of organizational chaos. You might find a cache of Ogawa’s negatives clearly labeled and in chronological order until, suddenly, they’re not. “We have a lot of work to do,” Bromberg explains. “We would need to go through the negatives and identify them.” That’s one reason Ogawa’s work has been overlooked and ignored by Seattle historians—it’s never really been accessible. “I’ve been working here twelve years and the problem with Elmer’s photo collection was that you couldn’t get to it because it had never been worked on,” Bromberg adds. “It was just the negatives in boxes. Really, you couldn’t use it.”

Like most archive projects, this one boils down to time and money. The call for donations in 2008 brought in a single check for one hundred dollars. The library was awarded a grant for $500, which helped to organize and label negatives and prints. Bromberg landed another grant for $20,000 to work on the photo collections of Ogawa and two other photographers. The money was used to put scores of Ogawa’s negatives in protective sleeves as well as to print some of the film.

Lately, University of Washington students have worked to digitize the images whenever time allows. Seated at workstations equipped with computers and scanners, students open boxes and leaf through photographs, looking for the more interesting photographs that might appeal to a broad audience. After each photograph is scanned, students type in whatever information they can find—date of the photograph, where the photograph was taken, or what kind of event the photograph depicts (usually found on the negative sleeve)—and upload the information to the Web.

“We will not put up all the photos because there are about twelve thousand and some are similar views of the same thing or completely unidentifiable,” Bromberg explains. “Someday, we will get a finding aid done for the collection. The finding aid will describe all of the images in the collection, and have hyperlinks to all the photographs that are digitized. That is, if we get a grant or some funding to help get it done.”

At the end of our meeting, Bromberg pauses to reflect on Ogawa. “His photos are interesting,” she says. “They have this kind of cool feel to them. I just love them.”

Perhaps one day more people in Seattle will love them too.

Todd Matthews is editor of the Tacoma Daily Index, an award-winning journalist, and the author of several books. His journalism is collected online at wahmee.com.