By Morf Morford

Tacoma Daily Index

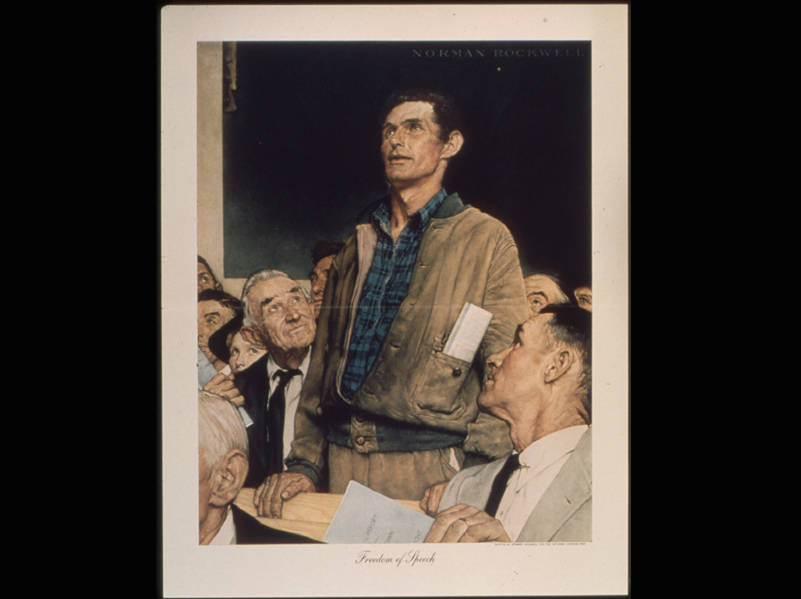

We honor and memorialize people who share our ideals and stand up for what they believe.

Or at least we say we do.

When we live among those people, or they live anywhere among us, we are rarely so idealistic or even certain of our own values and beliefs.

Standing up for your beliefs, after all, is only noticeable when it is a contrast to everyone, and everything, else.

Standing up for what everyone else believes and value takes no courage.

Opposing what everyone else opposes takes nothing except the inertia of going along with the crowd.

Standing up for one’s beliefs literally means to have beliefs and values distinct from everyone else.

And, when it comes to many crucial issues, or even to keep our minds and opinions from becoming conformist jelly reflecting what everyone else thinks, opines and believes, what’s the point of just ratifying what everyone else says?

It can be a bracing experience to embrace, and defend, an unpopular opinion – or even just consider a point of view from a perspective not usually considered.

When you think about, as few of us seem to do, that’s actually the only opinion worth considering. The “other” position, the one that everyone already holds and agrees on, is already fully represented.

Something like cultural gravity pulls us along, until someone, usually an annoying person, points out something obvious about what we all believe and take as normal, something we were perfectly fine with, until they had the audacity to point out how toxic or destructive it really was.

We might thank them for it; a decade or century later. But for now, when they have the misfortune of living among people like us (which happens to be true in every generation) they are just causing trouble and “rocking the boat”.

Our nation, for example, is founded on high and idealistic principles, ideals and principles so high in fact, that some of us are willing to die to defend them.

“Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” is a well-known phrase in Declaration of Independence perhaps first among these values and ideals. This simple, uncomplicated phrase gives three examples of the universal, non-negotiable rights which the Declaration says have been given to all humans by their creator, and which governments are obligated to protect. Like the other principles in the Declaration of Independence, or other defining phrases, like “liberty and justice for all” this phrase (and what it represents) is not legally binding.

It is just morally binding.

Or you’d think it would be.

And you’d think that when we departed from, or lapsed in our adherence to our deepest beliefs, that correction would be welcomed – and acted upon.

Actually, you CAN count upon course correction being acted on – but it is not likely to be in a way most of us would expect.

And almost always at a level of intensity we might not have expected.

I used to attend an all-white church in Tacoma.

It didn’t describe itself that way, and would have denied to the death that it was.

There were a few families and individuals of color that attended or were even members. And, for the most part, they were treated graciously as far as I could see.

But the message was clear that, though they may be welcome, this would never be “their” church.

Many years ago, at least ten years ago, our church had a meeting where we attempted to face our “institutional” hence invisible, if not near automatic, instinctual tilt toward racism, our American history wrapped around the residual stain of slavery came up. A woman I had respected for her intellectual and historic background stood up in defense, so she thought of our national history by proclaiming “Our Founding Fathers KNEW slavery was wrong.”

I’m not sure what her point was, and she did not have the opportunity to expand on her statement.

There’s a word for those who know the right thing to do, but refuse to do it: and it is not one I’d like applied to myself, or the Founding Fathers of our nation.

Bank robbers and car thieves “know” that what they are doing is “wrong”.

“Knowing” something is wrong and still doing it, or personally profiting from it, will never be a sign of courage or personal morality.

Anyone, then, who knows the right thing to do, yet fails to do it, is guilty of sin. – James 4:17

Most of our Founding Fathers and every president before Abraham Lincoln (at some time in their lives) held slaves.

Their moral failure back then, haunts our educational, political and economic system to this day.

Everything from urban design (zoning and red-lining for example) to school-room discipline is impacted by those attitudes and values nearly “hard-wired” into our systems.

Like my church back then, we are quick to deny “being racist” – even if our denials are contradictory or absurd.

I used to have a relative (by marriage) from the “greatest generation”. When the issue of implicit (barely recognized) racism came up, she, like my friend at church had, what she thought was the ultimate, iron-clad defense “I’m not racist! I had a Black maid.”

No one (I presume) wants to be defined as being “a racist”, but if your defense is that you once (or more than once, in this case) had a Black maid, your argument is quite convincing – but not in the way you probably intended.

Would she have ever had a white maid? Would she see a Black person in anything other than a subservient position?

She, like the church I once knew (and most blatantly racist people) are just fine with the “existence” of people of color – as long as they “know their place” and stay in it.

It is when they presume that they have the rights of the rest of us (as testified in the Declaration of Independence, among other places) that we (and they) have a bit of trouble.

Standing up for what we believe is virtually always admirable, but rarely easy.

One well known business mentor, as he hears business proposals, looks for one thing – not similarity to existing businesses (like the “Uber of everything) but the gut-level, immediate reaction (that is rarely positive) (https://mentorphile.com/2018/04/17/is-your-idea-crazy-enough/).

In other words, the question is not, is your idea crazy, but is it crazy enough?

Consider any idea or technology that upended or defined the past decade or two. How many of them were “crazy” ideas?

From smart phones to Amazon, to Starbucks to Netflix, who of us back in, say 1995 or so, would have put money into any of them?

Looking back, of course, it would have been a “smart” investment. But back then, it was completely crazy.

Standing up for what you believe will always look “crazy” – but it is always worth doing, and we desperately need to hear those voices leading the way.

As science fiction writer Arthur C Clarke reminds us;

“Every revolutionary idea seems to evoke three stages of reaction. They may be summed up by the phrases:

(1) It’s completely impossible.

(2) It’s possible, but it’s not worth doing.

(3) I said it was a good idea all along.”

Those life-changing ideas may (and will) challenge our biases and habits, but that, by definition, is what it means to grow. And like the technology that has become second nature to us, we will marvel that we could have lived without it.