Not to be missed – not for everybody

By Morf Morford

Tacoma Daily Index

The current exhibit at the Washington State History Museum is what every museum exhibit should be: evocative, thought-provoking, unsettling, solidly historic, regionally rooted and locally relevant.

But it is certainly not for everyone.

State authorized incarceration will never be terribly attractive or inspiring.

In fact the early days of incarceration in Washington, perhaps like our prison system still, reflects our cultural ambivalence, if not outright neglect of what happens after a judicial verdict.

The artifacts of this exhibit are grim reminders of how our attitudes towards prison – and prisoners – has vacillated over the years.

Are prisoners capable of, in need of, or beyond rehabilitation? Have inmates abdicated any or all legal or even human rights? Is imprisonment punishment or retribution? Can inmates be used for any economically productive labor with all profits going to the prison owner – essentially as slave labor?

Is there any system or program that actually does rehabilitate – in other words, is there any system anywhere in the world – that allows the inmate to leave prison as a better, healthier and more productive worker and citizen?

One of the striking, though not immediately recognized, features of the exhibit is how purely American it is.

By American, I mean the peculiar mix of idealism, pragmatism, fear and avoidance that most of us still have when it comes to principles of punishment and incarceration. Do we want to punish – or heal – those who violate our laws? Do we just want them as far from us as possible? (If so, an island prison is nearly ideal – except that it is expensive.)

If prisoners are the “bad” people in this social equation does that mean that guards, prison staff and the warden are inherently “good”?

How many movies or television series have featured sadistic prison guards or horrific programs (too close to the truth) of medical or “scientific” research done on inmates – as if they were as expendable as laboratory mice?

I had a student many years ago at Pierce College who worked part time as a guard at McNeil back when it was a federal prison. He emphasized that there was little to no difference in moral character based on “which side of the bars” one stood on.

An additional irony is that this grim, mostly crumbling complex of aging concrete and rusting iron is in a stunningly beautiful setting.

The island itself is mostly pristine and lush, with the Olympic Mountains to the west and the Cascade range to the east. And of course, Sound and island views all around.

The prison complex is quite tiny – mostly occupying a small space on the southern side of the island. There is also a little space about mid-island that is used. The rest is almost all wilderness.

There are several homes – used by prison staff and their families for decades – now abandoned – and being reclaimed by nature – mostly blackberry bushes and rodents.

At one point there was even an elementary school on island.

For decades the prison was largely self-supporting with orchards, vast gardens, dairy herds and even its own slaughter house for island raised beef.

McNeil Island might be forgotten and neglected, but it is not far away.

The prison building can be seen easily from Steilacoom – and even from Chambers Bay – or even from the Narrows Bridge.

This exhibit, however, is not for everyone. It is almost more of a guided meditation than a museum presentation.

The artifacts are dense with unspoken – or even unspeakable – stories: stories perhaps best left untold even as they cry out for our attention.

Here’s one story that deserves telling –

Alvin “Creepy” Karpis, a Prohibition-era gangster named “Public Enemy #1” by the FBI from 1934-1936, had been incarcerated on Alcatraz and relocated to McNeil when Alcatraz closed in 1962.

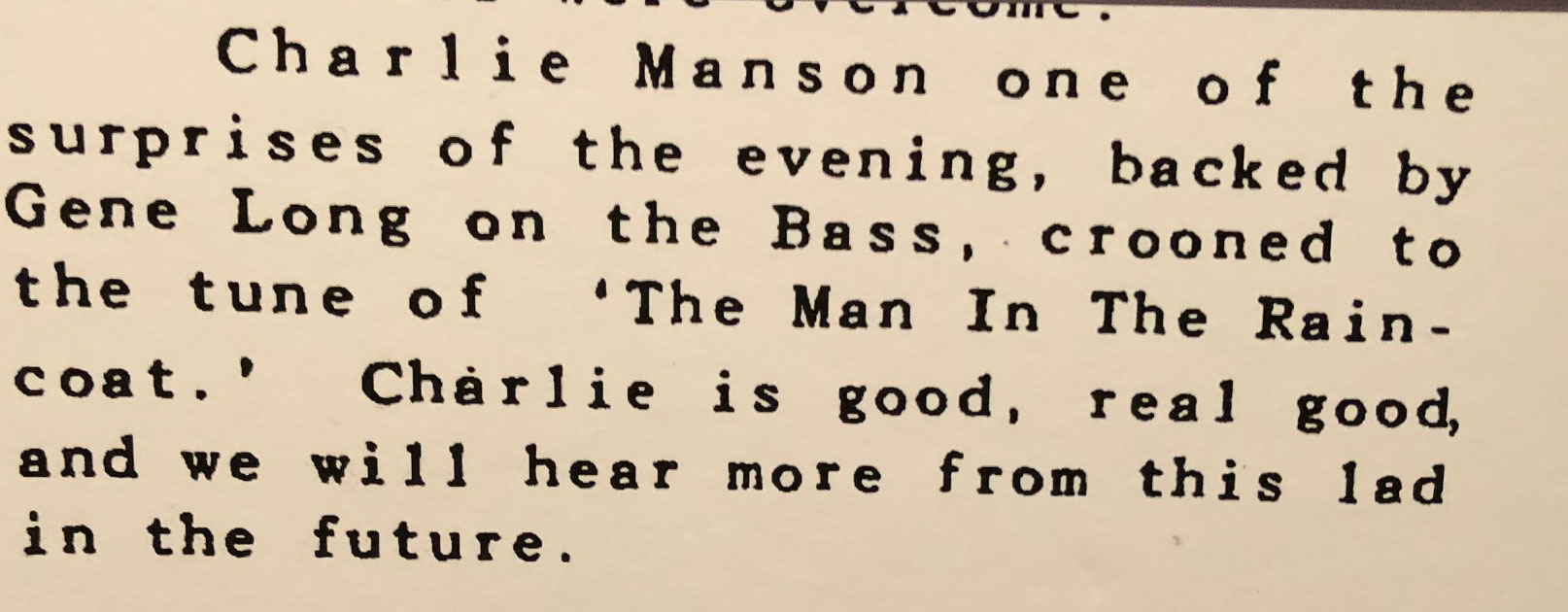

A few years later he had a young cell mate – a charismatic, musically talented young man, “state raised” in a series of orphanages, reform schools and foster homes.

This young man was named Charles Manson. Al Karpis taught young Manson the guitar – and probably a few survival strategies.

**************

(1*) As usual, we are conflicted even about islands – are they the ultimate vacation escape or the perfect prison?

(2*) Reportedly, Manson’s girl friend (and mother of one of his sons) moved to Tacoma to keep in touch with him and the son attended Tacoma area schools, stayed in the area, changed his last name and, following his father’s musical interests, became part of Seattle’s “Grunge” music scene in the 1990s.

************

From the Washington State Historical Society:

The prison on McNeil operated far longer than the better-known Alcatraz island prison in California, yet after 143 years the isolated McNeil remains a mystery to many. When the state’s correctional center on the island closed in 2011, it was the last prison in the nation only accessible by air or water.

While McNeil’s history may not be widely known, many of us will recognize some of the prison’s better-known inhabitants, including: Charles Manson, incarcerated at McNeil Island Penitentiary from 1961 to 1966 for forgery; Robert Stroud, also known as the Birdman of Alcatraz, sentenced to 12 years at McNeil for manslaughter; Frederick (Fred) Emerson Peters, an impersonator, con artist and forger who signed checks as Theodore Roosevelt in the early 1900s and masqueraded as several celebrities of his time, sentenced to McNeil in 1924; Roy Gardner, one of the last “celebrity” train robbers, who was initially incarcerated on McNeil in 1920, escaped the island prison three times, and was ultimately moved to Alcatraz; Alvin Karpis, a Depression-era gangster and head of the Barker-Karpis Gang, named “Public Enemy #1” by the FBI from 1934-1936, incarcerated on Alcatraz and relocated to McNeil when Alcatraz closed in 1962.

“McNeil was first a territorial prison, then a federal penitentiary, then a state facility. Each of those phases is explored in its own section of the exhibition. Visitors will sense the feeling of containment in the transition spaces between each exhibit section, because the transitions are scaled to the prison cells of each era,” said the Historical Society’s Director of Audience Engagement Mary Mikel Stump.

The exhibition offers a rare opportunity to view artifacts including the 1,800 pound wrought iron entry gates to the prison, letters between a conscientious objector and his family, a violin built from wood scraps and crafted based on directions that were smuggled in, a well-used pay phone, art and furniture made at the prison, and much more.

The museum is also inviting the community to participate in a conversation about life after incarceration at a March 2 symposium on Saturday, March 2, from 1:30 – 3:30 PM. A moderated panel conversation will provide an opportunity to learn about the challenges and opportunities of re-entry after incarceration. The panel moderator is Mr. Omari Amili, author, community leader, and a 2019 Humanities Washington Speaker presenting From Crime to the Classroom: How Education Changes Lives. Following the panel discussion, join a facilitated exhibit tour and talk with others at a reception. The symposium is included with museum admission.

A companion photography exhibition, Reclaimed, provides a visual survey of how nature and the climate of Puget Sound have begun to overtake the built environment on the island since the closure of the McNeil correctional center. Both Reclaimed and Unlocking McNeil’s Past: The Prison, The Place, The People will be on view January 26 through May 26, 2019.

Further details at www.WashingtonHistory.org/mcneil and www.forgottenprison.org