By Morf Morford

Tacoma Daily Index

I live in a basic workman’s house built in the late 1920s.

I use the term basic because it lacks the flourishes of many houses in Tacoma built just a few years earlier.

My house has no stained glass, no inlaid imported tile, no servant’s quarters and no hidden passages or turrets.

It is a basic house. Built for living in; not for entertaining.

It is a house built for the average person who worked.

To show how times have changed, the previous sentence is code for a house a family with one non-professional wage-earner could afford.

A house one non-professional worker on one average income could afford barely exists now.

Up until recently, housing was considered a basic human need; by pretty much every culture anywhere for every era in human history.

No one used the term “housing is a human right.” No one needed to be told.

Basic, adequate, affordable, stable housing was one of the core assumptions of all of us.

We had “homeless” people before, but we rarely used the word “homeless” before 1980.

We used to call “homeless” people “transients” precisely because they were in transition, between things, temporarily dislocated.

We, and most of them, knew that being “homeless” was a temporary condition, one that, with the next job, the next ride out of town, the next letter from home would be taken care of.

Even for those “transients,” cheap housing was almost always available with boarding houses, the local “Y” or “flop houses” in every city.

Homeless “communities” as we see in virtually every major city in the world right now, only existed in times of crisis, like major economic depressions or wars.

These “camps” suddenly disappeared (essentially forever) once the crisis was resolved.

I think we all know that our “homeless camps” will not disappear forever – in fact we all know that they will be with us for a long, long time. They might even be a permanent aspect of every urban landscape.

It doesn’t need to be this way of course.

Homeless camps drag down real estate values, they are vectors for petty crime and serious disease.

And as much as urban legends tell us otherwise, no one wants to be there. No one intended to be there, and no one wants to stay there very long.

No resident of those camps feels safe, every single one of them feels exposed – exposed to the elements, to crime, to assault, to hunger, to cries in the night, even arbitrary civic laws or police activity.

Homeless camps are not a solution. No one wants to live in them and no one wants them in their neighborhoods.

The “solution” to homelessness is what it always was, before we had the fancy terms like “housing is a human right” or even “homelessness.”

The old saying about homeless people is that every person, every family, is on their own.

They are, and every “solution” to their dislocation is on its own too.

Every homeless person came from somewhere. A unique set of circumstances drove each one of them to a common, and desperate state.

It could be eviction, abusive home situations, substance abuse or a hundred other intolerable if not destructive experiences that led to their condition of homelessness. Many of them escaped horrible situations and simply have nowhere else to go.

For the most part, our responses to them, both personal and official, only add to their burdens. They are hounded, victims of “sweeps” (who could have come up with such a derogatory and dehumanizing term? We literally describe them as garbage and are offended when they “resist”) and are, like vermin, chased from one neighborhood to another.

We forget that the vast majority of the “homeless” are not far from home. Most of them lived, went to school, even worked not far from where they are now. And not that far from most of us.

And we are not far from them.

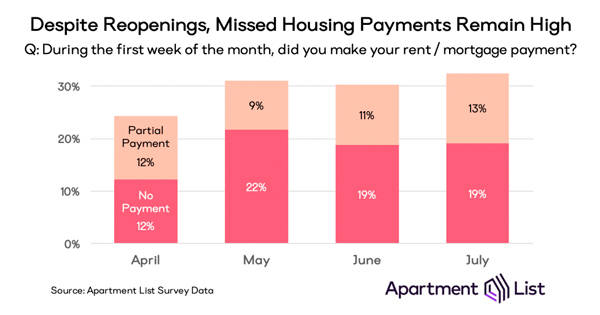

In July of 2020, over 30% of Americans have already or are expected to miss their housing payments.

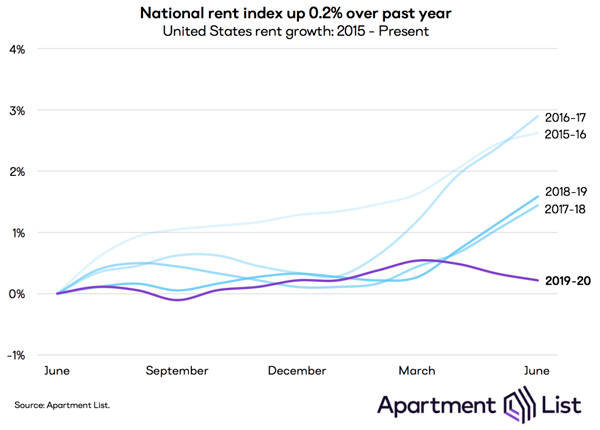

Rents, at super-high levels for years are moderating a little.

Those who follow housing see a massive increase in eviction rates – even though some municipalities have temporary restrictions on evictions.

We all know that this solution is temporary.

Along with the various other crises hitting our cities, neighborhoods, city budgets and housing infrastructures, a flood of homeless people at a time of pandemic and budget crunch could easily accelerate into a catastrophe beyond our control.

The previous “solution” has been to build more housing – more high-end housing.

I don’t know what “problem” constructing more high-end housing was supposed to solve, but it certainly was not homelessness.

The vast majority of those new units stood – and still stand – empty. There are vastly more homeless people, and yes, on paper at least, there is more housing available.

To put it simply, the math does not add up.

Housing does not need to be upscale; it does need to be affordable and available. As I write this, a news story rolls across the bottom of my TV screen; 8 million people have relocated because of current conditions.

Where do they all go? What are their housing options? What can they afford?

Paying for housing on one income should not be the extreme rarity it currently is.

Decent, even desirable housing should be accessible to the typical working person.

Recent events have highlighted the dilemma virtually every family faces; do they raise a family or both work to afford housing?

Almost all families feel like they must make the choice between family and career. One decision forecloses the other.

Families need the opportunity the original owners of my house had; one income should be enough to live on. Raising a family should not be an exclusive domain of the wealthy.

Home ownership used to be a central tenet of “The American Dream.” What have we become when so few have access to something as basic as housing?

Housing may not be a “human right,” but lacking housing does not make the homeless any less human, and our ever-growing and seemingly intransigent homeless population says far about us, and our laws and values, than it says about them.

Info/ chart source: Apartment List; see links for more information: https://www.apartmentlist.com/research/national-rent-data and https://www.apartmentlist.com/research/july-housing-payments. About Apartment List Rent Reports: Apartment List’s Rent Reports cover rental pricing data in major cities, their suburbs, and their neighborhoods. We provide valuable leading indicators of rental price trends, highlight data on top cities, and identify the key facts renters should know. As always, our goal is to provide price transparency to America’s 105 million renters to help them make the best possible decisions in choosing a place to call home. Apartment List publishes Rent Reports during the first calendar week of each month.