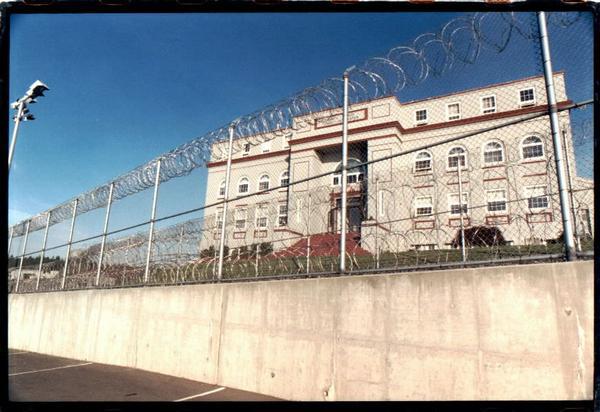

Closing the last island prison in the nation is an assignment filled with questions.

How do you maintain operations at McNeil Island Corrections Center while transferring staff members and relocating more than 200 offenders?

How do you move tons of medical equipment, a furniture factory, supplies, office furniture and records when everything has to be hauled on a small barge?

What do you do with the staff houses that are now abandoned?

How do you hand over the marine operations to a different state agency?

How do you archive the history of a prison that opened just a few years after the final gunshots of the Civil War?

The task list is 10 pages long, according to Washington State Department of Corrections (DOC) officials.

“It’s an enormous project with a very short timeline,” said Denise Doty, Assistant Secretary of Administrative Services. “The staff at McNeil Island is obviously impacted, but it takes a lot of effort by a lot of different divisions to close a unique facility like this.”

The DOC announced in November it will close McNeil Island Corrections Center by April 1 as a result of budget cuts. The agency had originally planned to close Larch Corrections Center near Vancouver but determined that closing Larch would not save enough money. DOC will save $6.3 million each year by closing the prison located on an island in south Puget Sound. It would have saved $2 million by closing Larch. The agency must reduce spending by nearly $53 million as a result of across-the-board cuts due to declining tax revenue. This will be the third prison the agency has closed within a year. DOC closed two minimum-security prisons last year — Ahtanum View Corrections Center in Yakima and Pine Lodge Corrections Center for Women near Spokane.

According to HistoryLink.org, an online encyclopedia of Washington State history, on Sept. 17, 1870, the federal government purchased 27.27 acres on McNeil Island for a federal prison, which officially opened in 1875. These 27 acres are the site of the main penitentiary complex today. The original McNeil Island cellhouse was built in 1873. DOC has operated the prison since 1981 when the state signed a lease with the federal government to take over the federal penitentiary which had been closed since 1976.

“The staff members there have heard for years that it was too expensive to operate on an island,” DOC Secretary Eldon Vail. “It’s simply the victim of a historic budget crisis.” Larch Corrections Center, a minimum-security prison located on Larch Mountain in Clark County, will go back to full capacity and house 480 offenders. It currently houses about 240 offenders. “This will save the most money without compromising the safety of our staff, the offenders and the public,” Vail added. “The budget crisis is causing us to make some of the most painful decisions in our agency’s history.”

The task force that is responsible for ending operations by April 1 includes representatives from nearly aspect of the agency: human resources, labor relations, capital programs, information technology, records, transportation and more.

Dick Morgan, who retired last year as Prisons Director, accepted a temporary assignment as the last Superintendent at McNeil Island. “It’s not as simple as locking the door and walking away,” Morgan said. “There are all types of regulations involved including fire marshals, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the U.S. Coast Guard. There’s a lot to consider.” Most of the living units are now closed as offenders have been transferred to other prisons. But because so many of plant operations are linked together it’s nearly impossible to close segments of the prison. “For example, the heating system is designed as a loop around the entire facility, so you can’t just cut off the water at one unit,” Morgan said. “It’s an all-or-nothing operation.”

Once the powerhouse is shut down the prison will not meet code requirements for safe occupancy. That will be the point of no return because the cost of bringing the buildings back up to code would be prohibitively expensive. There will be no water running in the sprinkler system and no electricity to turn on lights or heat buildings.

As for the ultimate fate of the prison buildings and the staff houses, that will be determined in part by what scavenging experts recommend in the coming weeks. “We want to salvage as much as possible,” Doty said. “I know, for example, that the old Superintendent mansion has some beautiful old wood that might be salvaged. Of course, getting everything off an island makes that job more difficult.”

In the meantime, the Human Resource staff continues to find job options for the staff members who remain at McNeil Island. Several other prisons kept positions vacant so most staff members have already found positions elsewhere in the agency. Some staff members, meanwhile, have requested to stay until the prison closes.

“There’s a sense of pride being the last one on the island,” Morgan said. “We’re trying to move as quickly as possible, but I can appreciate that. In fact, I kind of feel that way myself.”