By Morf Morford

Tacoma Daily Index

You’d think that after almost 250 years, we as a nation would have this voting thing figured out.

And you’d be forgiven for believing that 50 states that literally define themselves as being “united” would have a unified theory, or at least a set of agreed upon principles by which, in a self-proclaimed “democracy” citizens could express themselves and participate, without intrusion or coercion, as informed contributing citizens.

And you’d think that a Constitution that simply and clearly defines both the duty and the obligation to vote would be known by, and adhered to, by all.

And finally, you’d assume that any and all legitimate political parties would encourage and facilitate this ultimate right and responsibility of citizenship.

Unfortunately, at least in recent years, you’d be wrong on all counts.

In spite of the flurry – and hysteria – wrapped around voting rights and voting security and integrity, the Constitution is very simple. Three Amendments address voting and voting rights.

In contrast, a few states have taken it upon themselves to develop voting rights documents that approach hundreds of pages. Virtually of it is hyperbole and elaborate self-justification.

The premise of voting in a democracy is very simple; every legitimate citizen has the right to a vote.

Politicians can obfuscate, elaborate and even veer into incoherence if they like (and one gets the feeling that they must be paid by the word), but the premise could not be more simple.

In early 2021, you’d think that voting had just been discovered, or that vast organized voter fraud had been uncovered. Or even that a perilously close election had been decided with only a few votes making a difference.

You’d be wrong again.

Or at least you would be if you lived in a culture where facts mattered and votes, as for decades, were associated with registered voters and monitored by local districts and precincts.

There’s an old saying among politicians, “All politics is local.”

This holds true when it comes to issues from potholes to school funding to how ballots are distributed and tabulated.

Voter “fraud” is exceedingly rare. Voter mistakes are actually fairly common.

The vast majority of these are signature mismatches. It turns out that a signature is often neglected or is not exactly the same as the one on record.

This is far from fraud.

In fact if there is something you sign on a regular basis, a credit card receipt for example, do you sign it exactly the same each time?

If you are like me, or anyone I know, your full name and signature, are almost never an exact match.

Sometimes I use a middle initial, sometimes I don’t. Some occasions call for a full middle name, others don’t.

Sometimes I sign with a first initial and last name.

Sometimes I am rushed or inattentive, others times deliberately formal.

Like many people, I rarely use cursive and my “signature” is more like a hand printed version of how I usually write.

A few years ago a governor, with great fanfare, signed into law a strict “signature match” policy for voting.

Every aspect of the signature on the ballot was required to match completely the voter’s signature on file.

At the next election, the obvious occurred; the governor’s own ballot was disqualified.

Unlike politicians, how often are most of us required to officially sign a document? Once or twice a year?

My point is that my “signature,” year after year, election cycle after election cycle, will not often “match” my signature on file – especially if that signature was set up when I first registered to vote – many, uncountable years ago.

So, as is often the case after years of deliberate confusion and obfuscation, a review of the basics seems to be essential.

Here are the fundamentals direct from the US Government (https://www.usa.gov/voting-laws).

Article 1 of the Constitution gave states the responsibility of overseeing federal elections. Many Constitutional amendments and federal laws to protect (and for the most part, expand) voting rights have been passed since then.

In the U.S., no one is required by law to vote in any local, state, or presidential election. According to the U.S. Constitution, voting is a right and a privilege.

There are about 22 countries worldwide that have a compulsory voting but only 11 enforce it. These include Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Greece and many more.

Here in the USA, NOT voting in any given local, state or federal election is as much of a “right” as actual voting.

There are four Constitutional Amendments that impact voting rights and access.

In these few short amendments, be sure to note both the chronology and the deliberate precision as to who is included and who is not.

The 15th Amendment gave African American male citizens the right to vote in 1870. Some states used literacy tests, poll taxes and other deliberately race-based barriers to make it harder to vote.

The 19th Amendment, ratified in 1920, gave American women the right to vote. (Notice the fifty year difference between the 15th and 19th Amendments).

The 24th Amendment, ratified in 1964, eliminated poll taxes. These were special fees applicable only to African Americans to restrict them from voting in local and federal elections.

The 26th Amendment, ratified in 1971, lowered the voting age for all elections to 18.

That’s it.

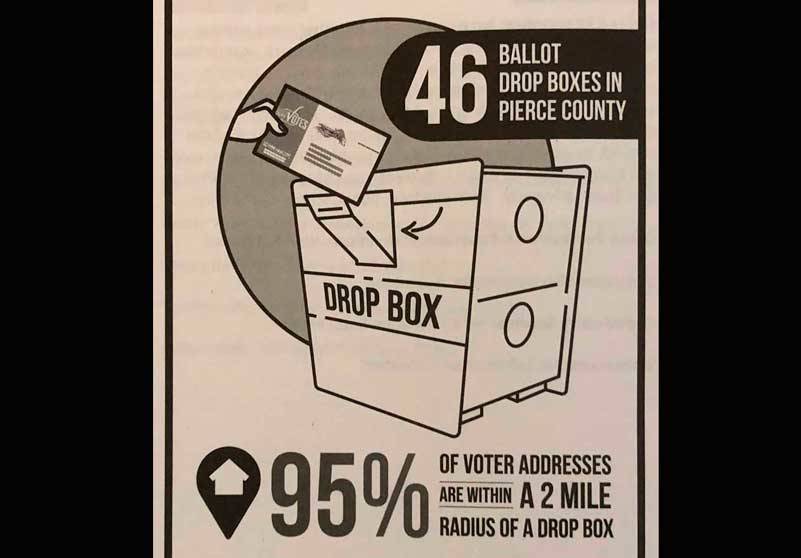

Nothing in the Constitution mentions vote-by-mail, advance registration, felony convictions or ballot drop off boxes.

For whatever reason, many politicians have come to believe that they have the “right” to decide who votes, and under what conditions.

They believe that politicians pick their voters.

The exact opposite is true and always has been. We, the voters pick the politicians.

And when they begin to believe that they can change the rules to keep themselves in power, they have confirmed that they are unfit for public office.